Artist in conversation: PETER CONSTANTINE

Peter Constantine is an emerging mixed-media artist, currently based in New York City. In his art Constantine works with stories and images linked to Greek Bronze Age hieroglyphs and languages thought to be lost in time. He is among the last generation of speakers of Arvanitika, a Greek sister language of medieval Albanian spoken in southern Greece, where he grew up. Among his subjects are the lost words and sounds of Arvanitika, as well as other forgotten languages of Greece and his work is breathing life into ancient cultures and systems of knowledge that have faced erasure.

He has participated in numerous group exhibitions around the world and his series of six works based on the Finnish epic, the Kalevala, is part of the permanent collection at the State Museum of Urban Sculpture in St. Petersburg.

He is also a writer, translator, and activist for a diversified linguistic ecosystem in our world, a Guggenheim Fellow and the recipient of two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships, the PEN Translation Prize and the National Translation Award, as well as literary prizes from Germany, Kosovo and Greece.

| Instagram |

What initially inspired you to become an artist, and how did you develop your unique style?

About a decade ago, the Russian artist, Dmitry Sokolenko, put together a collaborative art project focusing on the Kalevala, the national epic of Finland. To my great surprise he asked me to participate. The works I created for his project were granite and marble with images in polyurethane burnt onto the surfaces. The project was exhibited in several cities in Finland and then in St. Petersburg, Moscow, Berlin, and Paris. My first works ended up in Russia’s State Museum of Urban Sculpture in St. Petersburg. It was in this early project that I started combining images of people and symbols as I have continued doing.

In terms of subject matter, what themes or motifs do you frequently explore in your work, and what draws you to these topics?

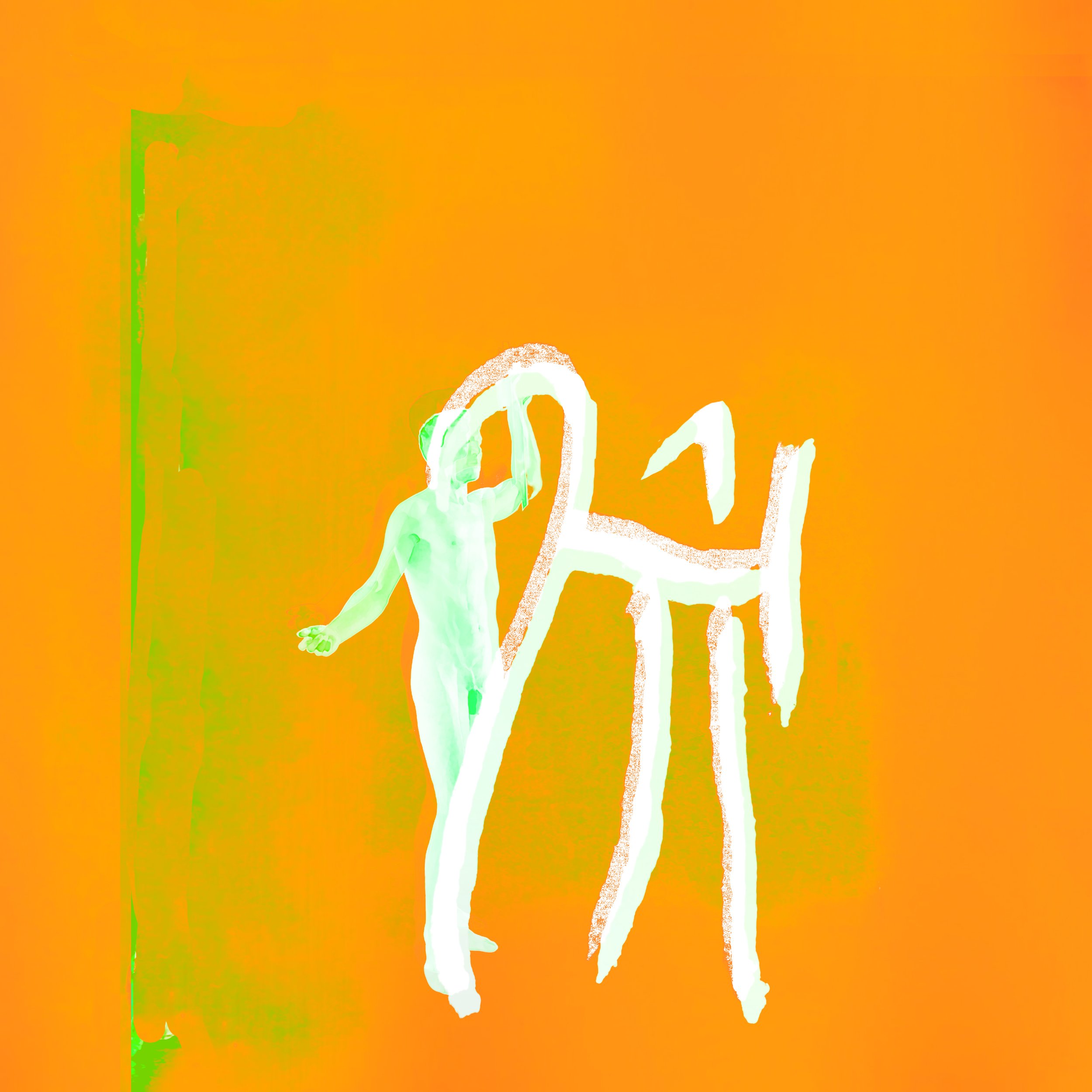

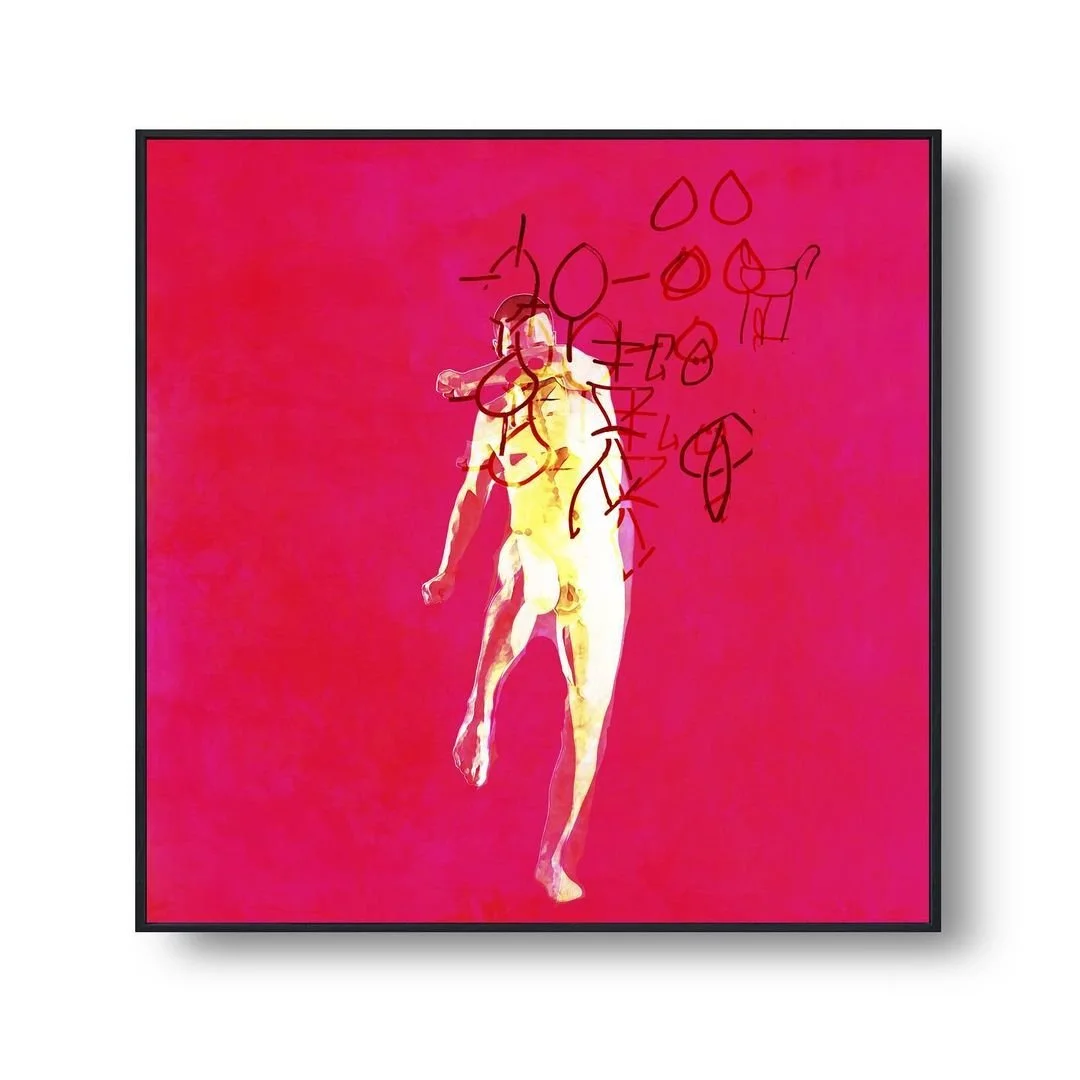

My current ongoing project focuses on bronze-age Greek hieroglyphs in which nude figures interact in various configurations with forgotten pre-Homeric sounds and words. The interactions of hieroglyphs and humans that I portray involve struggles with different power relationships; sometimes the humans, but usually the hieroglyphs, seem to have the upper hand. At the core of these struggles and confrontations is a quest to encounter and connect with forgotten words from forgotten languages that were spoken over millennia on the Greek peninsula and its islands.

Can you discuss a specific piece or project that challenged you as an artist, and how you overcome those challenges?

I like working on copper sheets that are very thin and pliable, just slightly more solid than foil. There are two challenges involved in this. One is that the copper crinkles, which I find can offer fascinating new dimensions to a work; a bigger challenge is that areas of the copper that are not covered by ink, acrylic, and wax will slowly oxidize, which dramatically changes an artwork over time. Some works I have sealed at various stages of oxidization in order to stop the process, but there is one work—a self-portrait with Mycenean bronze-age hieroglyphs—that I am letting oxidize, and plan to let oxidize indefinitely so I can experience its ongoing transformation and learn from this what new elements and factors such natural changes can bring to a work.

How do you stay connected with other artists and keep up with new developments and trends in the art world?

I’m interested in exhibits, though to my surprise I find myself almost exclusively focusing on artists’ uses of colour and texture. I also find Instagram a fascinating opportunity to follow the artists I admire who are working in different media.

How do you incorporate feedback from critics and audiences into your artistic practice, and how do you balance this feedback with your own artistic intuition?

At art exhibitions it is very useful to get personal feedback from people who are interested in buying or looking at my work. I have found that people are generally very kind and polite and will not take it upon themselves to give advice, but of course it is criticism and candid feedback that can be most useful. At an individual exhibit that I had in Paris last year, a well-known art collector was very angry when I told her I had used a mix of inks, wax, and chalk on a work she wanted to buy. She felt that the work would not last and grew extremely irate. One could say that she made a scene (somewhat to the amusement of the other visitors). She stormed out of the gallery, returned to look at the work once more, and then stormed out again without buying it, clearly very upset as she badly wanted the piece but didn’t trust its durability. I was so startled, that I forgot to tell her that I had washed over the work with water and that it would not fade, but her reaction was an important lesson in some of the concerns that buyers might have. The work was subsequently sold, but I felt bad that someone who had so passionately wanted it but was uncertain about its durability felt she could not acquire it. I’ve been subsequently more focused on such concerns, particularly in relation to some of my works on copper that continue to oxidize and consequently could be considered unstable. I want to keep on working and experimenting with oxidizing copper before I exhibit any of these works.

How do you stay motivated and inspired despite any setbacks or creative blocks you may encounter?

I have recently realized that I find myself most motivated and productive when I’m most busy with projects that are not related to visual arts. I then seem to manage to block out chunks of time and work in a very concentrated manner.

How has your interest in the Greek language influenced your artistic practice, and in what ways has it manifested in your work?

I grew up in Greece – my mother Austrian and my father British. We lived outside Athens and in the Peloponnese, in areas where both Greek and Arvanitika was spoken. So I grew up with these languages. Arvanitika, which shares a common ancestor with medieval Albanian, is one of the languages of Greece that is now severely endangered. Greek and Arvanitika, and the other disappearing native languages of the Greek peninsular are the main motifs of my current art projects. My works all contain the lost and forgotten words of the bronze-age Greek hieroglyphs, and the Linear A and Linear B writing of ancient Greece from the area where I grew up.

How do you feel about exhibiting your artworks with The Holy Art Gallery?

As I am originally from the UK and having grown up in Greece, I feel the fact that the gallery has its origins in both lands interestingly relevant. I am delighted by the idea that my works that are mixed media on aluminum will have a second life as digital images on large screens. That is an unintended and exciting new dimension to these works. I also very much welcome the idea of a broad new international audience seeing my work in art on loop.